Without action, coral reefs could disappear from Caribbean in 20 years.

In a comprehensive report of the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network (GCRMN), Status and Trends of Caribbean Coral Reefs: 1970-2012, a clear link has been established between the balance of herbivores and coral health in the Caribbean. Specifically, the parrotfish and the Diadema sea urchin, the former in sharp decline and the latter almost eliminated, are key components of a healthy reef eco-system. Broadly stated, the absence of sufficient herbivores on the reef has led to a large increase in algae. This algae is toxic and smothering the fragile coral ecosystem.

In a comprehensive report of the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network (GCRMN), Status and Trends of Caribbean Coral Reefs: 1970-2012, a clear link has been established between the balance of herbivores and coral health in the Caribbean. Specifically, the parrotfish and the Diadema sea urchin, the former in sharp decline and the latter almost eliminated, are key components of a healthy reef eco-system. Broadly stated, the absence of sufficient herbivores on the reef has led to a large increase in algae. This algae is toxic and smothering the fragile coral ecosystem.

Previously, it was widely suspected that the primary culprit behind coral reef degradation was global warming. Researchers looked at data for extreme warming events in 1998, 2005, and 2010. They found that there was no correlation between these events and subsequent coral loss. Actually, they found the opposite: “…the greatest losses in coral cover occurred at reef locations with less than 8 DHWs (degree heating weeks, the datapoint for extreme heating events).” This report concluded that “…local stressors have been the predominant drivers of Caribbean coral decline to date,” not global warming. It should be noted that the researchers didn’t eliminate ocean heating as a stressors on the reefs, especially for the Florida Keys, where they pointed out: “We caution that our results do not mean that extreme heating events are unimportant drivers of coral mortality due to coral bleaching and disease, as they clearly have been in….the Florida Keys.”

History of reef decline

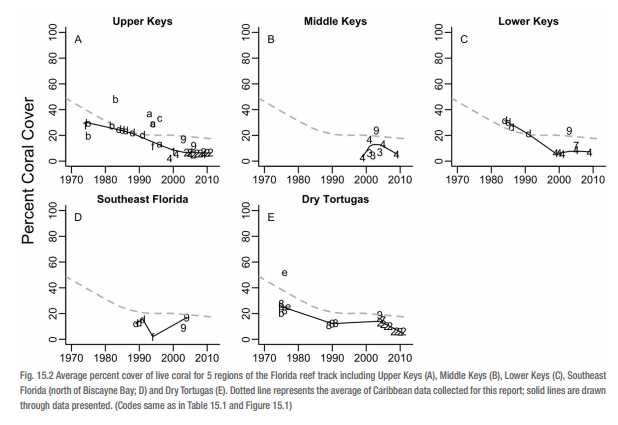

The GCRMN carefully analyzed 43 years of data and documented how coral coverage declined in three distinct phases:

- Phase One: a massive die-off of Acropora corals in the 1970s and 1980’s due to White Band Disease, possible caused by ballast discharges from ships transiting the Panama Canal into the Caribbean.

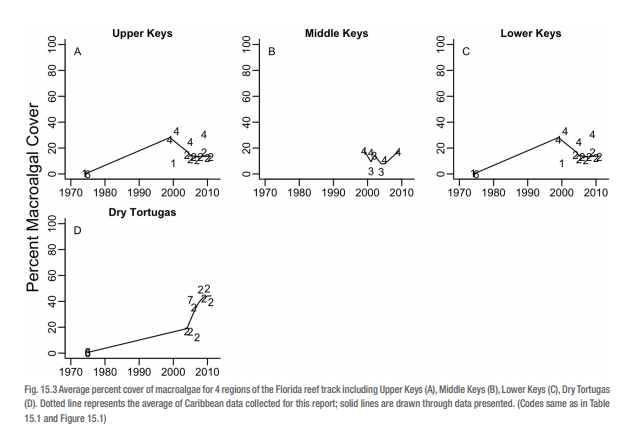

- Phase Two: a massive die-off of Diadema, the algae-eating urchins once ubiquitous on the reefs. Once again, a pathogen from the Pacific Ocean introduced via shipping, is considered the likely cause. The report shows that “Diadema mass mortality began only a few km from the Caribbean entrance of the Panama Canal. That, coupled with orders of magnitude increases in bulk carrier shipping int he 1960s and 1970s, strongly suggests that Diadema disease was introduced by shipping.” As the urchins died off, a simultaneous increase in algae was documented. According to the report, “macroalgae reduce coral recruitment and growth, are commonly toxic, and can introduce coral disease.”

- Phase Three: Continued die offs of urchins, along with increasing “overfishing, coastal pollution, explosions of tourism, and extreme warming events that in combination have been particularly severe in the northeastern Caribbean and Florida Keys where extreme bleaching followed by outbreaks of coral disease have caused the greatest declines.”

Parrotfish now key to Caribbean coral reef health

It is the parrotfish that the report concludes as particularly important to Caribbean coral reefs, as they are now the primary consumers of reef algae since the disappearance sea urchin.

Researchers observed that areas where parrotfish were overfished, such as Jamaica and the US Virgin Islands, had the highest algae growth and lowest coral cover. The report states, “All the historically overfished localities have low parrotfish biomass and low coral cover, and macroalgal cover is significantly greater than at less fished locations.”

The researchers also noticed that when parrotfish protections were put in place, coral began to rebound. The report states, “A similar result emerges from the partial recovery of parrotfish in marine protected areas in the Bahamas. Increased parrotfish abundance and size in the Exuma Cays Land and Sea Park resulted in a 2- to 3-fold increase in parrot-fish grazing intensity compared with unprotected sites. This increase in grazing further resulted in a decrease in macroalgal cover from 20-25% to 1-5% and a 2- to 3-fold increase in coral recruitment.”

Protecting and encouraging the reproduction of this fish is at the heart of this report’s conclusions and will require more marine protected areas, further education, and regulations on the use of spearfishing and fish traps.

Florida Keys – a “special case” of overuse and abuse

The report notes that in the Florida Keys, parrotfish are generally not taken. Researchers stated: “A recent study on the impact of grazing by herbivorious fishes found that herbivory levels were sufficient to maintain low macroalgal cover on the offshore reefs in the upper Florida Keys.” So what is happening here in the Florida Keys?

According to the report, the combination of unprecedented population and tourism growth in South Florida and its resultant pollution, coastal development, nutrient runoff from the Everglades and Florida Bay has “combined with regional and global environmental change to impact reefs along most of the Florida Reef Tract (FRT).

The report ominously concludes:

“…the FRT epitomizes a kind of worst-case scenario in which unprecedented population growth and inadequate governance and regulations have resulted in the critical endangerment of an entire coral reef ecosystem. Despite the positive and courageous actions of the Sanctuary, coral cover is well under 10% and declining. Much more stringent actions will be required for any hope of coral survival.”

While the City of Key West recently, and overwhelmingly, voted against dredging its ship channel to accommodate larger cruise ships, it is urgent that residents consider if there are already too many cruise ship passengers for the coral reef’s survival.

So what can be done?

The report has four major recommendations:

- “Adopt robust conservation and fisheries management strategies that lead to the restoration of parrotfish populations, including banning fish traps and fishing of any kind for parrotfish. Further, they recommend sever restrictions on spearfishing, gill nets, long lines, and all other destructive fishing practices.”

- “Simplify and standardize monitoring of Caribbean reefs, especially since this report showed how difficult it is to gather this important data.”

- “Foster communication and exchange of information. Many of the affected countries and regions were unaware of the work of other participants and frustrated about working in isolation of what was going on elsewhere.”

- “Develop and implement adaptive legislation and regulations to ensure that threats to coral reefs are systemically addressed, particularly threats posed by fisheries, tourism and coastal development as determined by established indicators of reef health.”

Failing to heed these conclusions and recommendations is not an option. The report concludes:

“Caribbean coral reefs and their associated resources will virtually disappear within just a few decades unless all the measures are promptly adopted and enforced.”